Dielectric

A dielectric is an electrical insulator that may be polarized by an applied electric field. When a dielectric is placed in an electric field, electric charges do not flow through the material, as in a conductor, but only slightly shift from their average equilibrium positions causing dielectric polarization. Because of dielectric polarization, positive charges are displaced toward the field and negative charges shift in the opposite direction. This creates an internal electric field that partly compensates the external field inside the dielectric.[1] If a dielectric is composed of weakly bonded molecules, those molecules not only become polarized, but also reorient so that their symmetry axis aligns to the field.[2]

Although the term "insulator" refers to a low degree of electrical conduction, the term "dielectric" is typically used to describe materials with a high polarizability. The latter is expressed by a number called the dielectric constant. A common, yet notable example of a dielectric is the electrically insulating material between the metallic plates of a capacitor. The polarization of the dielectric by the applied electric field increases the capacitor's capacitance.[2]

The study of dielectric properties is concerned with the storage and dissipation of electric and magnetic energy in materials.[3] It is important to explain various phenomena in electronics, optics, and solid-state physics.

The term "dielectric" was coined by William Whewell (from "dia-electric") in response to a request from Michael Faraday.[4]

Contents |

Electric susceptibility

The electric susceptibility χe of a dielectric material is a measure of how easily it polarizes in response to an electric field. This, in turn, determines the electric permittivity of the material and thus influences many other phenomena in that medium, from the capacitance of capacitors to the speed of light.

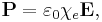

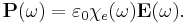

It is defined as the constant of proportionality (which may be a tensor) relating an electric field E to the induced dielectric polarization density P such that

where  is the electric permittivity of free space.

is the electric permittivity of free space.

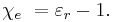

The susceptibility of a medium is related to its relative permittivity  by

by

So in the case of a vacuum,

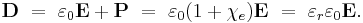

The electric displacement D is related to the polarization density P by

Dispersion and causality

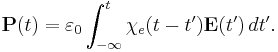

In general, a material cannot polarize instantaneously in response to an applied field, and so the more general formulation as a function of time is

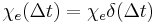

That is, the polarization is a convolution of the electric field at previous times with time-dependent susceptibility given by  . The upper limit of this integral can be extended to infinity as well if one defines

. The upper limit of this integral can be extended to infinity as well if one defines  for

for  . An instantaneous response corresponds to Dirac delta function susceptibility

. An instantaneous response corresponds to Dirac delta function susceptibility  .

.

It is more convenient in a linear system to take the Fourier transform and write this relationship as a function of frequency. Due to the convolution theorem, the integral becomes a simple product,

This frequency dependence of the susceptibility leads to frequency dependence of the permittivity. The shape of the susceptibility with respect to frequency characterizes the dispersion properties of the material.

Moreover, the fact that the polarization can only depend on the electric field at previous times (i.e.  for

for  ), a consequence of causality, imposes Kramers–Kronig constraints on the susceptibility

), a consequence of causality, imposes Kramers–Kronig constraints on the susceptibility  .

.

Dielectric polarization

Basic atomic model

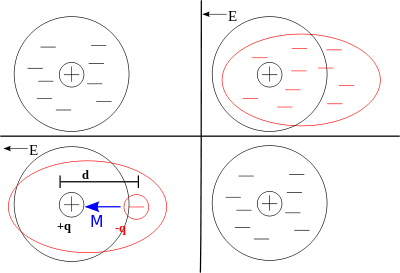

In the classical approach to the dielectric model, a material is made up of atoms. Each atom consists of a cloud of negative charge (Electrons) bound to and surrounding a positive point charge at its center. Because of the comparatively huge distance between them, none of the atoms in the dielectric material interact with one another . (Note that this model is attempting to describe not the structure of matter, but the interaction between an electric field and matter.)

In the presence of an electric field the charge cloud is distorted, as shown in the top right of the figure.

This can be reduced to a simple dipole using the superposition principle. A dipole is characterized by its dipole moment, a vector quantity shown in the figure as the blue arrow labeled M. It is the relationship between the electric field and the dipole moment that gives rise to the behavior of the dielectric. (Note that the dipole moment is shown to be pointing in the same direction as the electric field. This isn't always correct, and it is a major simplification, but it is suitable for many materials.)

When the electric field is removed the atom returns to its original state. The time required to do so is the so-called relaxation time; an exponential decay.

This is the essence of the model in physics. The behavior of the dielectric now depends on the situation. The more complicated the situation the richer the model has to be in order to accurately describe the behavior. Important questions are:

- Is the electric field constant or does it vary with time?

- If the electric field does vary, at what rate?

- What are the characteristics of the material?

- Is the direction of the field important (isotropy)?

- Is the material the same all the way through (homogeneous)?

- Are there any boundaries/interfaces that have to be taken into account?

- Is the system linear or do nonlinearities have to be taken into account?

The relationship between the electric field E and the dipole moment M gives rise to the behavior of the dielectric, which, for a given material, can be characterized by the function F defined by the equation:

.

.

When both the type of electric field and the type of material have been defined, one then chooses the simplest function F that correctly predicts the phenomena of interest. Examples of possible phenomena:

- Refractive index

- Group velocity dispersion

- Birefringence

- Self-focusing

- Harmonic generation

May be modeled by choosing a suitable function F.

Dipolar polarization

Dipolar polarization is a polarization that is particular to polar molecules. This polarization results from permanent dipoles, which retain polarization in the absence of an external electric field. The assembly of these dipoles forms a macroscopic polarization.

When an external electric field is applied, the distance between charges, which is related to chemical bonding, remains constant in the polarization; however, the polarization itself rotates. Because this rotation completes not instantaneously but in the delay time τ, which depends on the torque and the surrounding local viscosity of the molecules, dipolar polarizations lose the response to electric fields at the lowest frequency in polarizations. The delay of the response to the change of the electric field causes friction and heat.

Ionic polarization

Ionic polarization is polarization which is caused by relative displacements between positive and negative ions in ionic crystals (for example, NaCl).

If crystals or molecules do not consist of only atoms of the same kind, the distribution of charges around an atom in the crystals or molecules leans to positive or negative. As a result, when lattice vibrations or molecular vibrations induce relative displacements of the atoms, the centers of positive and negative charges might be in different locations. These center positions are affected by the symmetry of the displacements. When the centers don't correspond, polarizations arise in molecules or crystals. This polarization is called ionic polarization.

Ionic polarization causes ferroelectric transition as well as dipolar polarization. The transition, which is caused by the order of the directional orientations of permanent dipoles along a particular direction, is called order-disorder phase transition. The transition which is caused by ionic polarizations in crystals is called displacive phase transition.

Dielectric dispersion

In physics, dielectric dispersion is the dependence of the permittivity of a dielectric material on the frequency of an applied electric field. Because there is always a lag between changes in polarization and changes in an electric field, the permittivity of the dielectric is a complicated, complex-valued function of frequency of the electric field. It is very important for the application of dielectric materials and the analysis of polarization systems.

This is one instance of a general phenomenon known as material dispersion: a frequency-dependent response of a medium for wave propagation.

When the frequency becomes higher:

- it becomes impossible for dipolar polarization to follow the electric field in the microwave region around 1010 Hz;

- in the infrared or far-infrared region around 1013 Hz, ionic polarization loses the response to the electric field;

- electronic polarization loses its response in the ultraviolet region around 1015 Hz.

In the wavelength region below ultraviolet, permittivity approaches the constant ε0 in every substance, where ε0 is the permittivity of the free space. Because permittivity indicates the strength of the relation between an electric field and polarization, if a polarization process loses its response, permittivity decreases.

Dielectric relaxation

Dielectric relaxation is the momentary delay (or lag) in the dielectric constant of a material. This is usually caused by the delay in molecular polarization with respect to a changing electric field in a dielectric medium (e.g. inside capacitors or between two large conducting surfaces). Dielectric relaxation in changing electric fields could be considered analogous to hysteresis in changing magnetic fields (for inductors or transformers). Relaxation in general is a delay or lag in the response of a linear system, and therefore dielectric relaxation is measured relative to the expected linear steady state (equilibrium) dielectric values. The time lag between electrical field and polarization implies an irreversible degradation of free energy(G).

In physics, dielectric relaxation refers to the relaxation response of a dielectric medium to an external electric field of microwave frequencies. This relaxation is often described in terms of permittivity as a function of frequency, which can, for ideal systems, be described by the Debye equation. On the other hand, the distortion related to ionic and electronic polarization shows behavior of the resonance or oscillator type. The character of the distortion process depends on the structure, composition, and surroundings of the sample.

The number of possible wavelengths of emitted radiation due to dielectric relaxation can be equated using Hemmings 1st Law

where

- n is the number of different possible wavelengths of emitted radiation

is the number of energy levels (including ground level).

is the number of energy levels (including ground level).

Debye relaxation

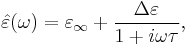

Debye relaxation is the dielectric relaxation response of an ideal, noninteracting population of dipoles to an alternating external electric field. It is usually expressed in the complex permittivity  of a medium as a function of the field's frequency

of a medium as a function of the field's frequency  :

:

where  is the permittivity at the high frequency limit,

is the permittivity at the high frequency limit,  where

where  is the static, low frequency permittivity, and

is the static, low frequency permittivity, and  is the characteristic relaxation time of the medium.

is the characteristic relaxation time of the medium.

This relaxation model was named after the chemist Peter Debye.

Variants of the Debye equation

- Cole-Cole equation

- Cole-Davidson equation

- Havriliak-Negami relaxation

- Kohlrausch-Williams-Watts function (Fourier transform of stretched exponential function)

Applications

Capacitors

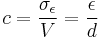

Commercially manufactured capacitors typically use a solid dielectric material with high permittivity as the intervening medium between the stored positive and negative charges. This material is often referred to in technical contexts as the "capacitor dielectric" [5] . The most obvious advantage to using such a dielectric material is that it prevents the conducting plates on which the charges are stored from coming into direct electrical contact. More significant, however, a high permittivity allows a greater charge to be stored at a given voltage. This can be seen by treating the case of a linear dielectric with permittivity ε and thickness d between two conducting plates with uniform charge density σε. In this case the charge density is given by

and the capacitance per unit area by

From this, it can easily be seen that a larger ε leads to greater charge stored and thus greater capacitance.

Dielectric materials used for capacitors are also chosen such that they are resistant to ionization. This allows the capacitor to operate at higher voltages before the insulating dielectric ionizes and begins to allow undesirable current.

Dielectric resonator

A dielectric resonator oscillator (DRO) is an electronic component that exhibits resonance for a narrow range of frequencies, generally in the microwave band. It consists of a "puck" of ceramic that has a large dielectric constant and a low dissipation factor. Such resonators are often used to provide a frequency reference in an oscillator circuit. An unshielded dielectric resonator can be used as a Dielectric Resonator Antenna (DRA).

Some practical dielectrics

Dielectric materials can be solids, liquids, or gases. In addition, a high vacuum can also be a useful, lossless dielectric even though its relative dielectric constant is only unity.

Solid dielectrics are perhaps the most commonly used dielectrics in electrical engineering, and many solids are very good insulators. Some examples include porcelain, glass, and most plastics. Air, nitrogen and sulfur hexafluoride are the three most commonly used gaseous dielectrics.

- Industrial coatings such as parylene provide a dielectric barrier between the substrate and its environment.

- Mineral oil is used extensively inside electrical transformers as a fluid dielectric and to assist in cooling. Dielectric fluids with higher dielectric constants, such as electrical grade castor oil, are often used in high voltage capacitors to help prevent corona discharge and increase capacitance.

- Because dielectrics resist the flow of electricity, the surface of a dielectric may retain stranded excess electrical charges. This may occur accidentally when the dielectric is rubbed (the triboelectric effect). This can be useful, as in a Van de Graaff generator or electrophorus, or it can be potentially destructive as in the case of electrostatic discharge.

- Specially processed dielectrics, called electrets (also known as ferroelectrics), may retain excess internal charge or "frozen in" polarization. Electrets have a semipermanent external electric field, and are the electrostatic equivalent to magnets. Electrets have numerous practical applications in the home and industry.

- Some dielectrics can generate a potential difference when subjected to mechanical stress, or change physical shape if an external voltage is applied across the material. This property is called piezoelectricity. Piezoelectric materials are another class of very useful dielectrics.

- Some ionic crystals and polymer dielectrics exhibit a spontaneous dipole moment which can be reversed by an externally applied electric field. This behavior is called the ferroelectric effect. These materials are analogous to the way ferromagnetic materials behave within an externally applied magnetic field. Ferroelectric materials often have very high dielectric constants, making them quite useful for capacitors.

See also

- Application of tensor theory in physics

- Clausius-Mossotti relation

- dielectric strength

- dielectric spectroscopy

- Dispersion (optics)

- EIA Class 1 dielectric

- EIA Class 2 dielectric

- electrorotation

- electret

- Havriliak–Negami relaxation

- high-k

- low-k

- leakage

- Linear response function

- Magnetic susceptibility

- Maxwell's equations

- Metamaterial

- paraelectricity

- QBD (electronics)

- RC delay

- Rotational Brownian motion

References

- Classical Electrodynamics,John David Jackson Published by Wiley,1998 ISBN7130932X,780471309321

- ↑ Dielectric. Encyclopedia Britannica

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Dielectrics (physics)". Britannica. 2009. pp. 1. Online.

- ↑ Arthur R. von Hippel, in his seminal work, Dielectric Materials and Applications, stated: "Dielectrics... are not a narrow class of so-called insulators, but the broad expanse of nonmetals considered from the standpoint of their interaction with electric, magnetic, or electromagnetic fields. Thus we are concerned with gases as well as with liquids and solids, and with the storage of electric and magnetic energy as well as its dissipation." (Technology Press of MIT and John Wiley, NY, 1954).

- ↑ J. Daintith (1994). Biographical Encyclopedia of Scientists. CRC Press. p. 943. ISBN 0750302879.

- ↑ States7113388 United States patent 7113388, Mussig & Hans-Joachim, "Semiconductor capacitor with praseodymium oxide as dielectric", published 2003-11-06, issued 2004-10-18, assigned to IHP GmbH- Innovations for High Performance Microelectronics/Institute Fur Innovative Mikroelektronik

External links

- Electromagnetism - A chapter from an online textbook

- Dielectric Sphere in an Electric Field

- DoITPoMS Teaching and Learning Package "Dielectric Materials"

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- "Dielectric". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Dielectric". Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

|

|||||